I chose Dan Flavin as minimalists have always appealed to me growing up, particularly musicians like John Cage, Steve Reich, Terry Riley, etc. Flavin’s simplicity was a legitimate statement in the 70’s and 80’s when he came to public attention.

Flavin was from NY, and in the early 50s was studying for priesthood. Many art critics and historians would later attribute some of the qualities of his work to this early religious interest, however, Flavin usually denies attaching any particular meaning to his work.

He later entered the military, the US Air Force, and was trained as an air weather meteorological technician. Through the army, he also got to study art in Korea through the University of Maryland. When he returned to the US in 1956, he attended multiple schools, eventually going to Columbia University for drawing and painting.

He became employed at the Guggenheim in 1959 originally as a mailroom clerk, then a guard, and then transitioned to an elevator operator at the MoMA.

His first significant works were a series called “Diagonals”. He rejected even the concept of a “work”, instead calling them “proposals” or “experiments”. Each diagonal has no further title, just the date it was installed (and sometimes a dedication or subtitle).

subtitle).

He rejected the labels of being called a minimalist (as most minimalists do, in my experience).

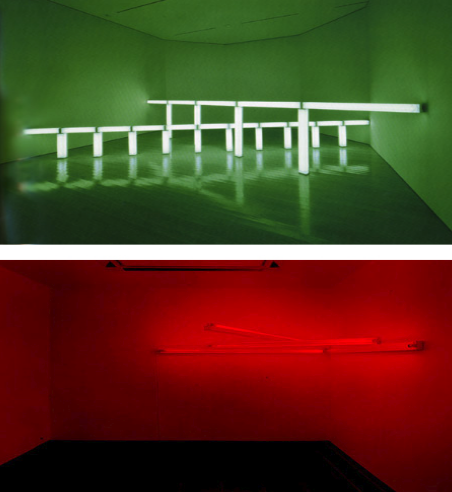

The diagonal appears “without mass” and “indeterminate volume”. Critics tend to say they are ephemeral and temporary since the fluorescent bulbs used eventually burn out.

Flavin’s use of reconstructed bulbs, instead of creating his own materials, falls in line with artists like Duchamp who installed reconstructed objects like a bicycle wheel or a toilet seat. Additionally, it allowed him to focus on other considerations like the surrounding space of the light, which becomes a part of the work itself.

The Diagonal of May 25, 1963 is described as “the diagonal of personal ecstasy”. Its “forty-five degrees above horizontal” position as one of “dynamic equilibrium”.

Light Vs Paint

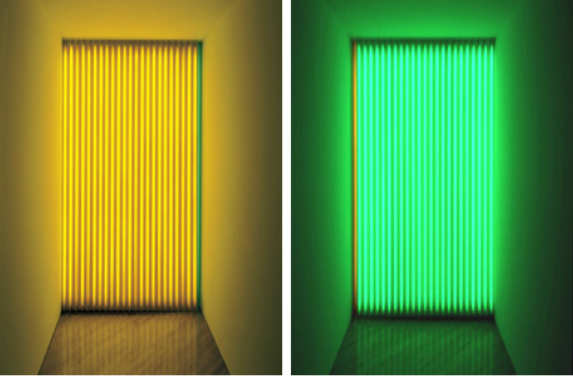

Part of Flavin’s experimentation is in how light behaves in almost opposite ways to paints and pigments. Blending pigments eventually results in black paint, while blending spectrums of light will eventually produce white light.

Th primary colors differ as well. Pigments are red, yellow, and blue. Light primaries are red, blue, and green.

Space & Architecture

Flavin’s work isn’t just the lighting he installs, it’s the space surrounding it. Putting a light in a corner, or a ceiling, has a deliberate purpose in the audience experiencing the physical space itself, and how the light occupies it.

Key Ideas

“It is what it is and it ain’t nothing else”

Flavin denied any particular meaning to his work, however many attach his background to priesthood to his work as representing ideas of religious conversion and spiritual epiphany.

Preconstructed materials

Avoided constructing his own materials, opting for commercially available fluorescent lighting. These lights are “perishable”, have a lifecycle, and thus are ephemeral.

Connection to Op Art: Emphasis on lighting and its effects

Translated this 1950s concept to sculpture.

Environment is part of installation

Flavin’s lighting tends to emphasize the space it occupies. The diffusing light from bulbs into the space is part of the work.

“ the ephemeral quality of the light itself is arguably completely contradictory to the otherwise industrial character of standard Minimalist materials like steel, aluminum, concrete, plastic, glass, and stone. Thus, Flavin’s legacy is less about his work as a significant Minimalist artist than it is in his ability to look beyond the movement”